Rats are wreaking havoc on a farm, so the farmer brings in an owl to hunt the rats. At first it works, but eventually the rats learn how the owl hunts. They adapt, and the rat population starts to rebound. Since the owl is no longer working, the farmer brings in a snake. The rats’ strategies for evading the owl do not work against this new adversary, and the snake successfully solves the rat infestation.

What do rats, owls and snakes have to do with cancer treatment? Actually, they provide the perfect analogy for the “double-bind” cancer treatment that could potentially change how we take on this disease.

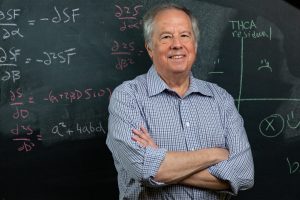

This theory is being applied by Robert Gatenby, M.D., of the Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute. Because tumor cells evolve to become resistant to certain treatments, we have to keep them on their toes with differing therapies.

This theory is being applied by Robert Gatenby, M.D., of the Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute. Because tumor cells evolve to become resistant to certain treatments, we have to keep them on their toes with differing therapies.

“We have good therapies in a lot of cancers now, and the initial response is frequently excellent,” said Gatenby. “But the problem is the cancer develops resistance. By doing that, the cancers, even when they look like they are in remission, can recur. The cells become resistant to the therapy, and once you get to that point, it’s very hard to gain control of the tumor again.”

It is currently standard practice to use cancer drugs at the maximum tolerated dose continually until the cancer starts to show regression. Because there are about a billion cancer cells in a single gram of a tumor, cancer cells have a tremendous amount of genetic variation, which means a tremendous number of opportunities to evolve resistance to a treatment. Gatenby wondered whether doctors could delay that resistance by dialing back the intensity of the therapy, thus reducing the pressure for cancer cells to adapt.

By studying how and when cancer cells develop resistance, Gatenby aims to create a new strategy to put cancer in a double bind. The idea is that doctors can first use standard treatments, perhaps at a lower dose, to get a patient into remission, then follow that with different types of therapies to keep them there.

A 2016 Designated Grant from the V Foundation gave Gatenby’s team the support they needed to test their theory. In their first clinical trial, focused on prostate cancer, they saw that cutting a chemotherapy drug’s dose by half or more actually extended the effectiveness of treatments from 14 months to more than 30 months, with 25% of patients stable after more than five years, an extremely high number for this type of therapy.

The research suggests that in some cases, less is more when it comes to cancer treatment.

Gatenby says the approach could work for many cancer types. His team is currently testing a similar strategy with teenagers facing sarcoma, a cancer for which the double-bind could potentially offer a cure.

The team’s early successes have given Gatenby a great deal of optimism about the future.

“I believe we are making tremendous strides, and by integrating evolutionary dynamics into cancer therapy, we can begin to control one cancer after another before we master this disease,” said Gatenby. “I think we will have substantial control of cancers in this next decade, and I would not have said that ten years ago.”

This optimism, and the theories and therapies that bring it about, are possible because of research funded by people like you. The “Don’t Ever Give Up” spirit of V donors and supporters continues to fund research that brings more hope and saves more lives.